British Medical Journal

Written by Lucy Howard, a blogger at Mrs H’s favourite things.

The British Medical Journal (BMJ) is defined by its mission statement which is “to work towards a healthier world for all.” Its print edition has been around for nearly 180 years and it is respected as a hugely influential international research journal. The articles produced by the BMJ are highly respected and influence clinical practice, research, education and government around the world.

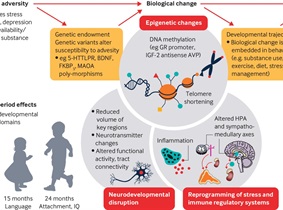

Recently the BMJ has produced an article showing how toxic stress in childhood can have impacts that last a lifetime. And how this adversity can be particularly linked to Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD).

The authors of this article are hugely respected in their field of research. The author, Professor Charles Nelson is a Professor of Paediatrics at Harvard Medical School. He has over 25 years of experience working in the field of developmental cognitive neuroscience and one of his current fields of research is in the effects of early adversity on brain and behavioral development. His collaborators on this article include Nadine Burke Harris, Surgeon General of California, who appears in the documentary “Resilience” (https://kpjrfilms.co/resilience/), a film about the links between toxic stress and hormones that wreak havoc on the brain and the body.

We currently work closely with the Center on the Developing Child at Harvard University and much of their research underpins the evidence base for Mindful Emotion Coaching and Adverse Childhood Experience (MACE).

The article is a must-read and a huge amount of learning can be gained from reading it. A particular quotation of interest is:

‘More attention also needs to be paid to individual differences. Different people respond differently to the same stressors. For example, only a minority of children who experience trauma or maltreatment go on to develop enduring psychiatric disorders; and some children develop physical health disorders such as asthma whereas others will not. In addition, individual differences exist in biological sensitivity to stressors: for example, children identified as shy or inhibited early in life may be more vulnerable to stressors than children with more robust temperaments and who are less fearful of novelty and are more predisposed to anxiety as adults.’

You can read the full article from The British Medical Journal here: